Before we learn another language, we assume that all other countries’ art must be more or less the same as ours. We assume it is coincidence that makes Shakespeare English, Molière French, Murakami Japanese or Sor Juana Inès de la Cruz Mexican. But then we learn a little. We learn nouns and verbs and adjectives. We learn quite how hard it is to translate anything well, let alone a story. We learn, in the end, that context is as necessary to writers and their work as water is to a fish.

To start reading French literature, then, is to immerse yourself in a new way of thinking. This new way of thinking requires us to be flexible; even the best Medieval English scholar would have to put aside their expertise in order to enjoy Medieval French work, because the expectations, the tropes, the context are all different. This means it can be hard to know where to start – we learn about English-language authors almost from birth, we know what we enjoy and what we don’t. Opening up a new culture of literature, you’ll have to start again. You have to read a little of this, a little of that, construct a new idea your literary tastes. In doing so, you discover new beauty and new horror. New ways to root for a hero and new ways to hate a villain. This is what makes it all so worthwhile, after all.

Without further ado, here are 6 (old!) French plays to read to get you started on your journey with French theatre, but also to get you thinking. Most of this I like, some I don’t. Some hold ethics close, others are designed to push us. All are best seen on stage, but still worth reading!

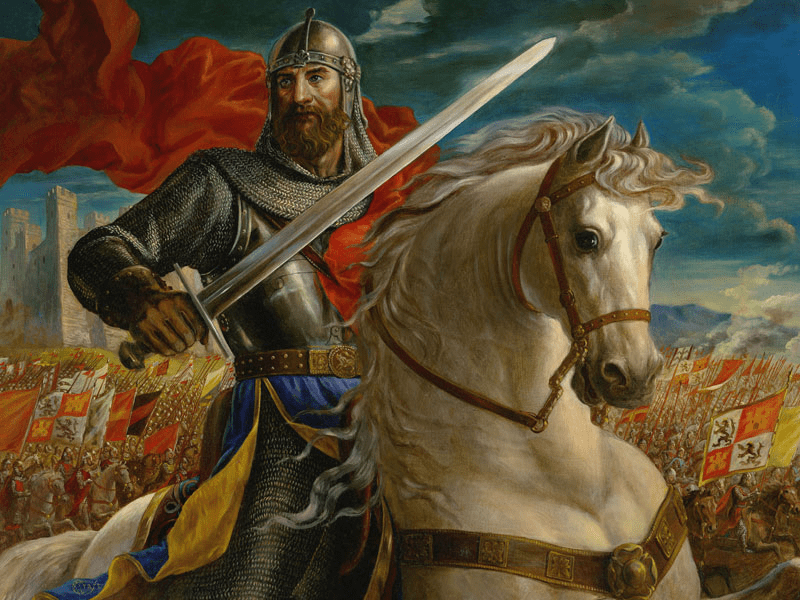

- Pierre Corneille: Le Cid (1637):

Le Cid is one of those plays that just gets better when you realise what kind of world it was born into. It is nothing shocking to a modern audience; we have no scruples when it comes to writers breaking the so-called ‘rules’ of theatre. But to Corneille’s contemporaries… it’s hard to imagine a play making a bigger splash!

At first glance, the play is nothing new: it is simply the story of lovers and the perils they face together. The full impact hits you at a second glance. The play pushes audiences to their limits as they root for the heroine, Chimène. Controversial in the 1630s for the display of immoral sentiment in the last scene and for its ‘untragic’ ending, the play was condemned by Richelieu, an official with power over the part of the government responsible for language and culture. Ironically, this also drove popularity up in time with the play’s infamy. I guess audiences have always thrived on scandal! But it is not only the play’s 17th Century popularity that makes it worth a read – what started as a discussion of women’s conflicting loyalties to parents and lovers gains an additional layer in the modern day, as we consider male accountability, the politicisation of wifeliness and our relationship with violence in drama.

2. Pierre Corneille: Horace (1640)

Hands up who likes a bit of gore! Well, not me. Luckily Corneille’s next play followed a few more theatrical rules than Le Cid, and avoids showing any violence on-stage. But that doesn’t mean it has any less impact! Being Corneille, the playwright could certainly not keep to allll the rules of theatre. Following the controversy of Le Cid, Corneille dusted himself right back off again and set about to write another morally ambiguous hero to keep us guessing. But it is not this hero – Horace – that I’m most interested in.

In the interests of placating the theatrical purists of the time, Corneille chose to following the ‘unity of place’, a rule of tragedy that insists that the whole drama should take place in one setting so as to make the plot more believable to a stationary audience. Despite the military themes of the play, Corneille nevertheless selected Horace’s home as this setting. Why should I care about that, you may ask. Well,why should anyone care that an honoured hero from ancient times is uniquely depicted within the confines of his house? That it’s the domain of women – housewives, daughters, servants alike, and not a place associated with men that’s used? Corneille’s presentation of heroes pushes the boundaries of masculine identity and asks as to consider: what really is a hero, anyway?

3. Molière: L’école des femmes (1662)

Nothing like a bit of good old-fashioned sexism to fire up the passions! Reading l’École des Femmes I was very, very conscious that the ending that would make or break it for me. Luckily my efforts were rewarded. Surprinsingly modern in his discussion of women and wives, Molière puts love front and centre, a force to be reckoned with by any man who should wish a woman to marry for anything less. For fans of Italian Commedia dell’Arte, Molière brings a plethora of tropes to the table. We have the insipid master of the house, comic servants and desirable heroine to complete the picture. Yet, the play remains strikingly French.

All this being said, I do have my qualms about the play’s conclusion. Initially, I found it far too reliant on coincidence. Then, I decided the conclusion was justified and entirely based on the situation set up in Act 1. Now, I’m somewhere between the two. So let’s talk about it! What do you think?

4. Jean Racine: Bérénice (1670)

This is the story of the original love triangle: two men, one woman, and the future of two nations at stake. As readers, we are used to stories like Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet, where parents and ruling powers forbid lovers from being together. Even tragedies like Phèdre emphasise rulers’ potential to accept or deny any given relationship for a host of moral and legal reasons. Bérénice takes things a step further.

From the beginning, it is made clear that the state is at the heart of the romance – Titus, Bérénice’s lover, has come to power and must at all costs do what is right for his country. But where does that leave Bérénice? Herself the exiled ruler of a competing state, how could she possibly be united with her enemy? The characters’ conflicting desires and the growing pressure to exert self control and put others before the self sets the tone for Racine’s play.

5. Jean Racine: Phèdre (1677)

Reading Phèdre at uni was a bit of a full-circle moment for me; the mock interview I did before I was accepted involved an extract from the play, and studying it properly took me back to my 17 year old self. I remembered that I was living the dream I’d had in sixth form. The same cannot be said for Phèdre herself. If anything, Racine’s play explores broken dreams!

Set in Trézane, a land that has long lost hope of Phèdre’s husband, King Thésée, returning from war, it seems Phèdre is close to death. Harbouring a secret (and somewhat œdipal!) desire for her stepson, Phèdre recieves advice that would ruin her should her husband return from the apparent dead. But what is to be done? The story of desperation, adultery, desire and advantage, the story of Phèdre inevitably ends in tragedy. It pulls at your heartstrings and puts audiences into the shoes of one with no good options left. This is a perfect play for those who need catharsis; it does not seek to reassure, it does not idealise that which we cannot have. Yet there remains a spark of passion all the way to the end that reminds us of the good that has always existed in the world.

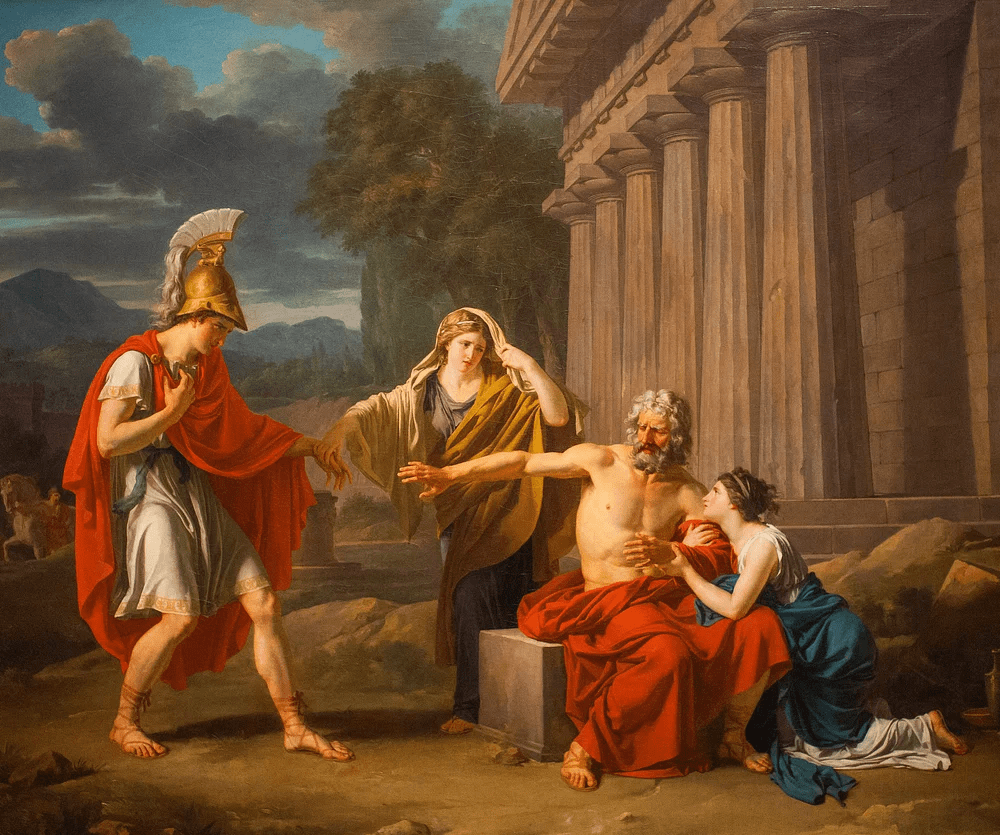

6. Voltaire: Œdipe (1718)

Œdipe – Oedipus – you know, that guy. The one we’ve all heard of and who Freud described so confidently. But how many of us know the tragedy itself? Like many of the plays here, Voltaire’s version of Oedipus is just one of many. Like many, it reformulates and reemphasises the parts of the story deemed most significant by the writer. But this version is one that sent ripples throughout the 18th Century artistic world for its daring.

Previously, depictions of Oedipus had highlighted fate, lost hope and other uncontroversial aspects of the tale. This was not the case when it came to Voltaire’s reimagining! Choosing to scandalise his way into popularity, Voltaire emphasised the incest the play is now so famous for. Not only this, but he emphasised incest right under the nose of the Regent and the Duchesse du Berry, his daughter, with hom he’d long been rumoured to be having an affaire. Put like this, it’s little wonder Voltaire spent time in prison as a result of certain comments about the Princess! Nevertheless, scandal breeds attention and attention trails popularity along behind. Whatever scandals and whatever the facets of the play the moralists scorned, it nevertheless took its place amongst the greats from French literary history.

So there they are, 6 French plays. They have all pushed me further in my French learning journey, and I hope they’ll push you, too! Whether you read them in translation or in the original French, there’s so much to take even from a few pages. They all reveal a little of the past; through them, we see gossip, scandal, appetite for tragedy and desire to see beauty represented on stage, even at times when the political realities were far less enchanting. We see the depth of human nature and the ironic layers of society, both back then and now.

Leave a comment